Volume Resuscitation Guide: When to Use What Products

In emergency and critical care medicine, few decisions carry as much immediate weight as how to restore circulating volume. The right choice of fluid, given at the right time, can mean the difference between stabilization and deterioration. Yet with so many products available—crystalloids, colloids, blood components—the decision is rarely straightforward. This guide walks through the principles of shock recognition, assessment, and product selection, illustrated with real-world cases and easy-to-scan reference graphics.

Understanding Shock and Volume Loss

Shock is not a diagnosis in itself but a syndrome of inadequate tissue perfusion. The underlying mechanism guides our therapeutic choices.

The Body’s Response to Volume Loss

Initially, compensatory mechanisms kick in: tachycardia, vasoconstriction, and activation of RAAS and ADH systems to preserve circulating volume. These adaptive responses buy time, but once decompensation sets in—hypotension, altered mentation, oliguria, lactic acidosis—aggressive resuscitation is essential.

Assessing Volume Status

No single parameter gives the whole picture. Clinicians must combine clinical signs with monitoring tools:

Perfusion checks: capillary refill, mucous membrane color, pulse quality

Organ perfusion: urine output (>1 mL/kg/hr is reassuring), mentation, extremity temperature

Advanced measures: central venous pressure trends, lactate clearance, base deficit

🩺 Clinical Pearl: In unstable patients, trends (e.g., falling lactate, improving urine output) are more valuable than single numbers.

Choosing the Right Fluid Product

Crystalloids: The Foundation of Resuscitation

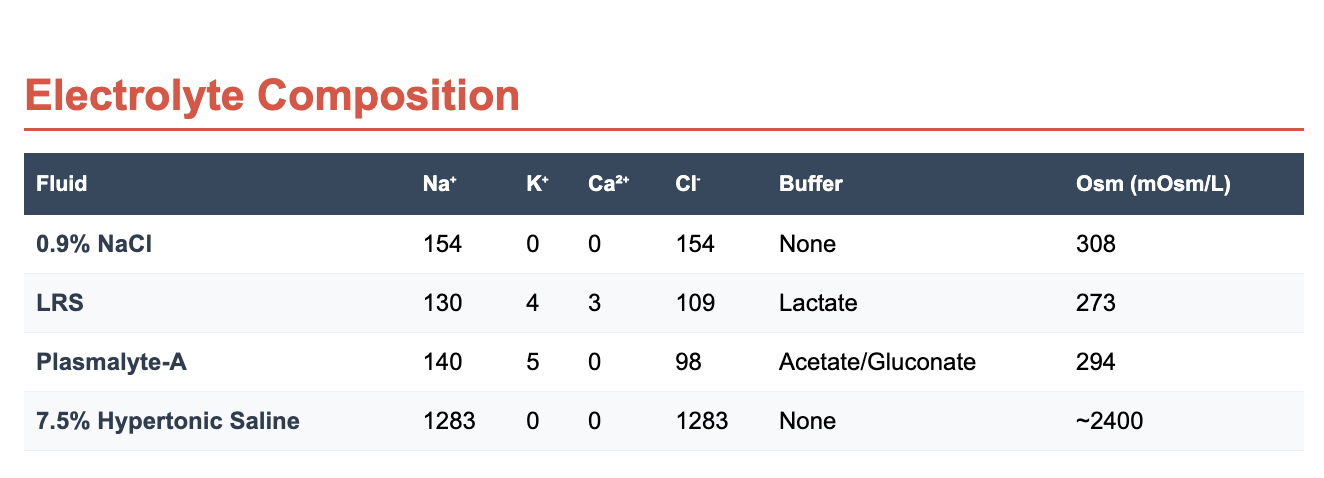

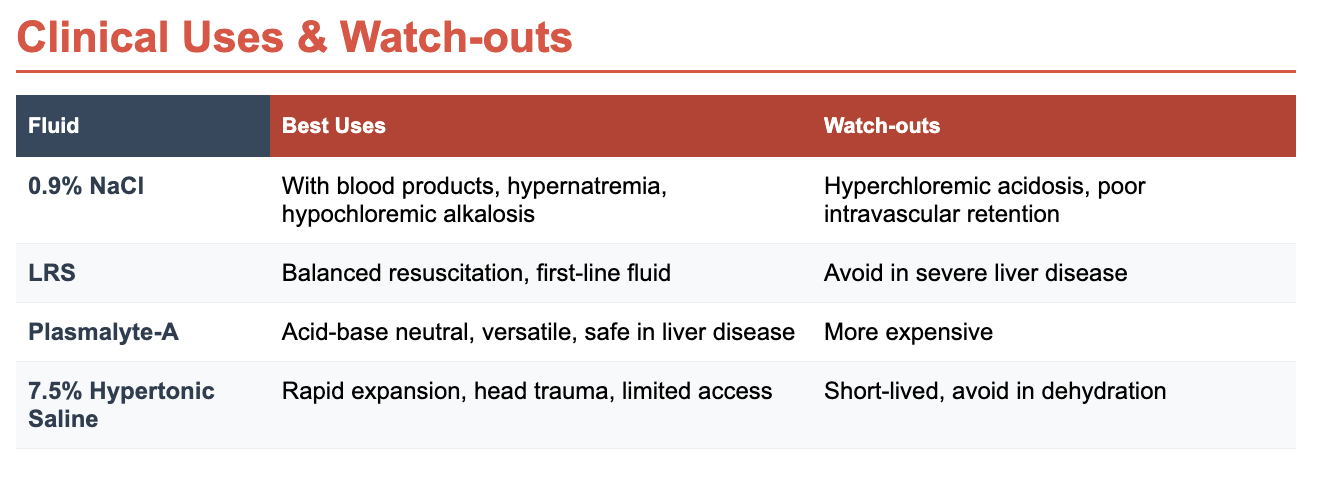

Balanced crystalloids such as Lactated Ringer’s Solution (LRS) and Plasmalyte-A are the first-line choice for most resuscitations. They restore volume rapidly, are inexpensive, and mirror physiologic electrolyte composition. Normal Saline remains useful with concurrent blood products or specific metabolic disturbances but risks hyperchloremic acidosis if overused.

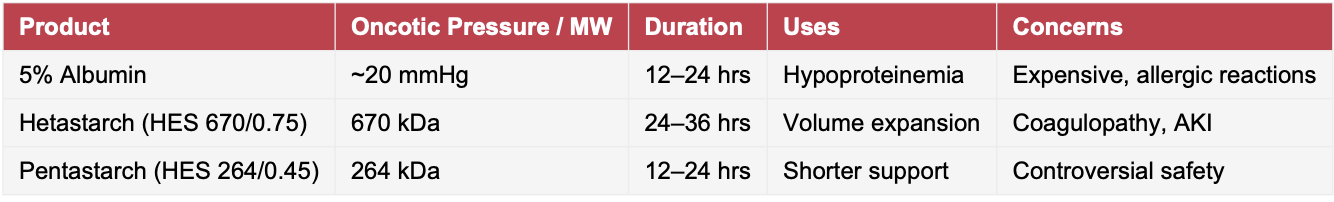

Colloids: Filling the Oncotic Gap

Natural colloids like albumin provide oncotic support but are expensive and occasionally immunogenic. Synthetic colloids (hetastarch, pentastarch) persist longer intravascularly, but concerns about coagulopathy and kidney injury limit their role. Today, colloids are best reserved for hypoalbuminemic patients or those who cannot tolerate the volumes of crystalloid required for stabilization.

Blood Products: Replacing What’s Lost

When anemia or hemorrhage are present, crystalloids and colloids cannot replace oxygen-carrying capacity or clotting factors. That’s when blood products become lifesaving.

Clinical Decision-Making in Action

Case Study 1: Hemorrhagic Shock

A 4-year-old Golden Retriever is rushed in after being hit by a car. Pale mucous membranes, weak pulses, and abdominal distension point toward intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Initial boluses of LRS (20 mL/kg) provide only transient improvement. A PCV of 18% and rising lactate (6.8 mmol/L) confirm severe blood loss. Blood products are prepared, and the patient undergoes emergency splenectomy after transfusion of pRBCs and crystalloid support. The dog recovers well, underscoring the principle: replace what’s lost with the right product at the right time.

Case Study 2: Septic Shock

An 8-year-old German Shepherd presents with pyometra, high fever, and shock. Crystalloid boluses improve perfusion, but lactate remains elevated. Fluid therapy is calculated to correct both dehydration and ongoing losses, while antibiotics and surgical source control address the underlying infection. This case highlights that fluids are necessary but never sufficient alone in distributive shock.

Case Study 3: Cardiogenic Shock

A 12-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel collapses with pulmonary edema from advanced mitral regurgitation. Here, aggressive boluses would be dangerous. Instead, small 2–3 mL/kg aliquots are trialed with CVP guidance, alongside furosemide, oxygen, and positive inotropes. This vignette reminds us that not every shock patient needs—or can tolerate—the same fluid strategy.

Monitoring and Troubleshooting

Resuscitation doesn’t end with fluid delivery. Vigilant monitoring is key:

Immediate response: improved mentation, pulses, capillary refill.

Short term (1–6 hrs): lactate clearance, PCV/TP checks, urine output.

Long term (6–24 hrs): electrolyte balance, coagulation status, renal function.

Complications such as volume overload, electrolyte derangements, or dilutional coagulopathy must be recognized early and corrected promptly.

Conclusion

Effective volume resuscitation requires both speed and precision. The foundation is crystalloids, but colloids and blood products play pivotal roles in select scenarios. The art lies in matching the product to the pathology—knowing when to expand, when to replace, and when to withhold. Clinicians who remain vigilant in monitoring and flexible in approach will give their patients the best chance at recovery.